Right Action and Self-Discipline

in the Theosophical Movement

Carlos Cardoso Aveline

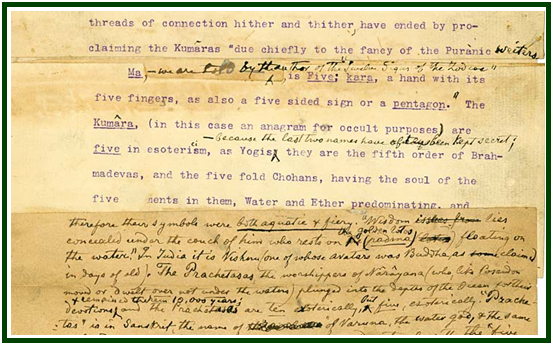

An example of proof-reading made by Helena Blavatsky during the preparation of

“The Secret Doctrine”. The fragment corresponds to pp. 577-578, volume II of the book.

[ Source of the image: Pasadena Theosophical Society ]

Since ancient time, the frontline of philosophical schools has been kept alive by editorial work, including research, writing, proof-reading and publishing. It has been so both in the East and the West, in Vedantic and Platonic literature alike.

The modern theosophical movement is no exception to the rule. Its main founders were notably its hardest-working authors, translators, researchers and editorial workers. The fact is well-documented that as long as the masters of the wisdom were in direct touch with the movement, they themselves took part in editorial tasks and actively helped the work of publications like “The Theosophist”.

The original Pedagogy of the Masters and Helena Blavatsky recommends a living process of research and study in which the dead-letter memorization is avoided.

The seemingly endless effort in proof-reading philosophical texts – among other tasks – is a form of training. It develops abilities like patience, perseverance, flexibility, attention and concentration. Planning and the right use of time and energy are critically important.

Editorial work forces the student to research and expands the contact of his soul with the ideas discussed in the texts. Being an altruistic effort, the process has many an element of Karma Yoga. The practice teaches humbleness and self-examination, since the student will have to see his own mistakes on a daily basis, and if he is lucky he will have his mistakes shown by friendly readers and persons of good will.

These are some of the reasons why the inner vitality of the esoteric movement directly depends on the importance ascribed to the process of research and writing, while all the individuals involved try to expand both the quality of the work and the altruism of their motivation.

A theosophical association that is not centered on the active search for knowledge ceases to be a community of learning and becomes a community of automatic believers. Its official truths are subject to political negotiation and quietly arranged according to institutional interests.

When Courtesy Replaces Research

While political activity is normally based in corporate interests and superficial opinions, leading-edge research questions old established ideas and destroys attachment to mental routine.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, politics and organized belief have had too much power in the theosophical movement. In the various corporations, research, the practice of the teaching and the search for consistency became uncomfortable for the dominant order in the various corporations.

In the 21st century, the larger and more bureaucratic associations of the theosophical movement are governed by political processes and not by a living unfoldment of advanced study and research. In the esoteric circles which are large enough to be governed by politics, the Karma Yoga of altruistic action is less important, in defining leadership, than the politically correct smile and the art of looking like a saint. While this rosy atmosphere dominates in many an esoteric group, the true theosophical movement follows the example given by its founders.

A Practical Lesson from HPB

Helena P. Blavatsky teaches through her life. She did not spend her days making exercises in public relations. She challenged organized ignorance and fought the causes of human pain. Although her life was an uninterrupted practice of austerity, she adopted no idle form of self-discipline. She followed the discipline of self-sacrifice for a humanitarian goal, and was an editorial worker.

In 1883, during the theosophical attempt to create in India a daily newspaper which would be named “Phoenix”, Alfred P. Sinnett questioned the effectiveness of HPB’s office.

She then revealed to Sinnett some of the circumstances under which the theosophical work has to be done, if the goal is to defeat mental routine and transmit the ethics of universal wisdom:

“I would like to see you undertake the management and editing of Phoenix with two pence in your pocket; with a host of enemies around; no friends to help you; yourself – the editor, manager, clerk, and even peon very often, with a poor half-broken down Damodar to help you alone for three years, one who was a boy right from the school bench, having no idea of business any more than I have, and Olcott always – 7 months in the year – away! Badly managed, indeed! Why we have made miracles in rearing up alone, and in the face of such antagonism, paper, Society, and business in general. (…..) Please remember that while you in the midst of all your arduous labours as the editor of the Pioneer used to leave your work regularly at 4 after beginning it at 10 a.m. – and went away either to lawn tennis or a drive, Olcott and I begin ours at five in the morning with candle light, and end it sometimes at 2 a.m. We have no time for lawn tennis as you had, and clubs and theatres and social intercourse. We have no time hardly to eat and drink.” [1]

The above lines help describe the life of disciples and aspirants to wisdom.

Personal comfort is not their priority; and Damodar K. Mavalankar, whose life constitutes the most brilliant success story in the theosophical movement of all time, is here frankly described by HPB as outwardly “half-broken down”.

Countess Wachtmeister Helps Blavatsky

Every editorial task becomes a probationary process, as far as it occurs in the realm of classic theosophical ideas. One’s struggle with words unfolds on various levels of consciousness at the same time. The contrast among these different layers of reality provokes considerable challenges.

The study, the reading and translation of a theosophical text are therefore multidimensional actions which must be performed once and again from several standpoints. Each time one resumes the work with a text, the vision and understanding of its contents may turn out to be considerably enriched, bringing new inferences and other insights.

In her book on Helena Blavatsky, Sylvia Cranston reproduces the testimony of Countess Wachtmeister, who assisted HPB as she wrote “The Secret Doctrine”.

The Countess says:

“One day (…), when I walked into HPB’s writing room, I found the floor strewn with sheets of discarded manuscript. I asked the meaning of this scene of confusion, and she replied: ‘Yes, I have tried twelve times to write this one page correctly, and each time Master says it is wrong. I think I shall go mad, writing it so often; but leave me alone; I will not pause until I have conquered it, even if I have go on all night.’ I brought a cup of coffee to refresh and sustain her, and then left her to prosecute her weary task. An hour later I heard her voice calling me, and on entering found that, at last, the passage was complete to satisfaction, but the labor had been terrible, and the results were often at this time small and uncertain.” [2]

However, asking an advanced disciple to write again ten or fifteen times the same passage is not something that only a Master of the Himalayas can do.

The inner master, too – the voice of the consciousness of each student of authentic theosophy, whether he is advanced or has no experience – frequently demands a constant revision and corrections in something he writes, or in his daily actions.

For well-informed students, “to live is to make corrections”, and self-improvement is the best way of life.

Learning classical theosophy means identifying and overcoming errors all the time. There must be no feeling of “victimhood” about that. As the popular saying goes, “it is by making mistakes that one can learn”.

NOTES:

[1] “The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett”, TUP, Pasadena, CA, USA, 1973, 404 pp., see Letter XXVII, p. 57.

[2] “HPB – The Extraordinary Life and Influence of Helena Blavatsky, Founder of the Modern Theosophical Movement”, by Sylvia Cranston, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1994, 648 pp., p. 296.

000

An initial version of “The Yoga of Editorial Work” was published at “The Aquarian Theosophist”, April 2017, pp. 9-11, with no indication as to the name of the author. The article was published as independent text on 13 November 2017, being revised and expanded by the author on 12 July 2018.

000

On 14 September 2016, after examining the state of the esoteric movement worldwide, a group of students decided to found the Independent Lodge of Theosophists. Two of the priorities adopted by the ILT are learning from the past and building a better future.

000