A Psychoanalysis of Human History

Carlos Cardoso Aveline

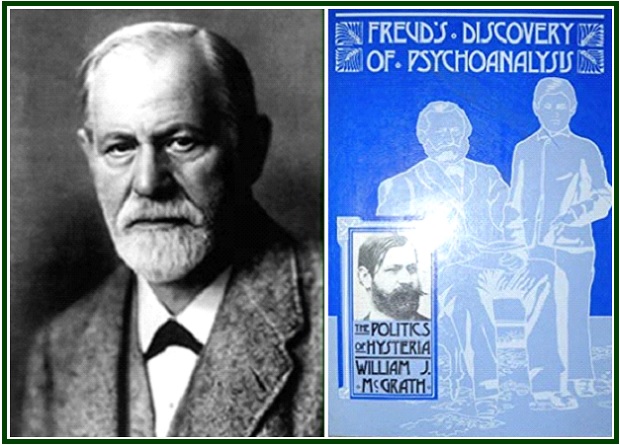

Sigmund Freud, and the front cover of McGrath’s book

Forgotten by many, the 1986 book “Freud’s Discovery of Psychoanalysis: The Politics of Hysteria”, by William J. McGrath, is a valuable tool if you want to avoid a planetary war and prevent unnecessary destruction.

Rather rare by now, the book makes it easier to understand many a political crisis and the disease of contempt for democratic decisions and institutions.

The chronic sickness is present in many a formally democratic country, side by side with an epidemics of repetitive personal attacks against leaders.

Describing the origin of Psychoanalysis during the years of Sigmund Freud’s study and research in Hysteria, the book by McGrath examines the evolution of the medical and psychological approaches to hysteria and the relation between this disorder and human history, including political and institutional life.

The sickness seems to have existed for ages.

Collective hysteria makes public opinion substitute slogans and mere propaganda for actual reasoning. Soon after that the process of organized hate emerges. Political or religious scapegoats are necessary for the collective feeling of discontent to be projected into some external object, which will produce a false relief.

While the blame game of present politics is ridiculous if seen from a rational point of view, it corresponds to an ancient practice, whose popularity is great in medieval, modern and “postmodern” times. It stimulates the perverted pursuit of sadomasochistic pleasure; the satisfaction derived from one’s own suffering and from making others suffer. The persecution against Jews and heretics in the Middle Ages was hysterical, and so are the various forms of political and social hatred in the 21st century – “progressive” or otherwise.

The dynamics of hysteria must be understood before it is abandoned. Common sense and the love of truth are enough to eliminate it. However, McGrath’s book invites us to the building of an intercultural view that is respectful of differences. The task belongs to theosophy, psychology, philosophy and other fields of knowledge.

By unmasking the mindless character of hysteria in family, in politics and every aspect of life, human karma or fate will be improved. It is useless to wait for “something to happen” that cures it from the outside. Each individual has the power and the means to become a healer of himself and the world. The peace of the soul will be restored according to the needs of evolution, and we all can help it take place. Big and small events are united and small seeds become large trees. A butterfly flaps its wings in Taiwan and a tornado occurs in London. The impact of the ocean waves in one part of the globe can be felt by the islands of other continents, as Victor Hugo writes in “The Toilers of the Sea”. [1]

Whenever hysteria spreads in society, sincere dialogue and moderation become the object of contempt. One must observe, then, the emotional process that flows behind unstable, nervous and automatic forms of intolerance.

Psychosis and Hysteria

Perhaps the main difference between psychosis and neurosis is that a neurotic sacrifices his basic instincts for the sake of preserving a realistic view of the facts. In social life, this is central to the democratic process. Such renunciation is also necessary in any balanced relationship among humans, or between human beings and the natural environment.

We sacrifice our personal wishes to preserve social harmony. We practice self-restraint in order to benefit others whom we love, for the sake of nature preservation, or out of respect for the reality of democracy and mutual help in our community and nation.

In the psychotic attitude, however, the individual sacrifices his feeling of respect for reality, in order to automatically follow his own instincts and desires. Truth, then, is left aside and moderation forgotten.

Psychoanalysis says that in neurosis we see “a loss of oneself”, or a self-sacrifice. In psychosis, one loses one’s relation to the objective reality. In neurosis, one painfully learns from his inner conflicts. In psychosis, the conflicts are projected into the outside world and the individual pretends he has no need to obey limits.

Freud writes:

“…One of the features which differentiate a neurosis from a psychosis [is] the fact that in a neurosis the ego, in its dependence on reality, suppresses a piece of the id (of instinctual life), whereas in a psychosis, this same ego, in the service of the id, withdraws from a piece of reality. Thus for a neurosis the decisive factor would be the predominance of the influence of reality, whereas for a psychosis it would be the predominance of the id. In a psychosis, a loss of reality would necessarily be present, whereas in a neurosis, it would seem, this loss would be avoided.” [2]

In a neurosis, the view of facts is distorted, while in psychosis the view of reality is simply suppressed, and no degree of frustration will be accepted. Fantasy takes the place of actual facts: hence the process of hysteria. In any psychosis, dissociation dominates and reason has scarce chances.

In social events like anti-Semitism, racism, terrorism and religious intolerance, psychotic attitudes are present and influential. Every form of systematic hatred in politics tends to place instincts above reason and is under the influence of hysteria. One must remember that hysteria means a childish condition of the soul. Small children did not have a chance yet to recognize the proper limits to their actions, which Life and Necessity inevitably impose. [3]

The complex relation between instinct and reason in human souls is a major factor in determining the future of civilization.

Since the last decades of 20th century, the widespread use of psychoactive drugs has been consistently stimulating the epidemic of psychotic attitudes and the loss of balance in the perception of reality.

The alternative, according to classic esoteric philosophy, consists in restoring the ability to be in harmony with the soul. He who listens to his conscience can listen to his fellow-citizens. On the other hand, he who can’t really pay attention to others is not able to learn the lessons taught by his own spirit.

An awakening soul enables the individual to see the law of equilibrium in operation and perceive the cosmic unity linking all parts of the universe. The soul teaches us harmony, and as soon as we have inner peace we see union and positive interaction unfolding among all living beings.

The State of the Nation and One’s Own State

Sigmund Freud documented the direct relation between one’s state of mind and the state of one’s nation.[4]

There is a double dynamics.

On one hand, the social and political landscape of the community is a central factor in determining the geography of one’s soul. On the other hand, the content of one’s mind gets naturally projected to the outside world, since our emotions and subconscious thoughts are the lens through which we look at the outside world.

Just like in our friends and adversaries, we see in our country that which is inside ourselves. The fantasy of dissociation is a disease, and at this point seven conclusions seem to be largely inevitable:

1) We must be happy with ourselves in order to transmit peace to others. Superficial harmony depends on the unstable winds of appearance and is therefore short-lived.

2) The politics of hatred leads nowhere, and so does the transformation of adversaries in permanent scapegoats. These are but mechanisms of hysterical escape from reality. No need to dwell on the famous examples of hysteria given by Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

3) It is no use for social movements to act like grown-up children who cry and yell while refusing to be responsible for their own actions, and keep ascribing to others – the “adults” – the power to decide on their own lives.

4) Conservative groups ought to avoid defeating themselves by behaving like immoral parents who don’t care for their own family and cheat those who are nearest to them. He who cheat others or take advantage of poor people is but deluding himself in the long run.

5) In a parliament as in a family, if honest dialogue is impossible and words fail to produce a common understanding of shared goals, it is the time to calmly unmask the presence of hysteria and nonsense. A firm serenity is necessary in order not to add fuel to the flames. Disaster will be avoided if the unmasking is promoted soon enough, with the adequate amount of strength and determination.

6) Effective leaders stimulate mutual respect. They set the example of voluntary simplicity, constructive attitude, good will and cooperation. It is the duty of all to be honest with their adversaries. These principles prevent the causes of corruption and avoid the source of social injustice, war and terrorism.

7) Since time immemorial, humanity’s growth in wisdom has been the central factor in History. Yet the learning of the soul takes place in spiral. Often painful, sometimes joyful, the process of learning dies and is born again in cycles – big and small. The most basic principles of life are forgotten from time to time and must be taught and learned once more in a thousand occasions. Therefore a theosophist would say: ‘he who does not have the courage to improve himself should not lose time pretending he wants to correct others. For the two things are inseparable. One must try to stop his own mistakes before furiously fighting the mistakes he thinks he sees in others. We have to know ourselves before we can really know other people. Self-control is better than controlling the external world.’

The well-written book by William J. McGrath gives us valuable elements to understand that hysterical attitudes tend to disappear in families, as well as local communities and nations, whenever real knowledge is attained and inner balance becomes firm enough to be transmitted to others by example.

My Mind to Me a Kingdom Is

Peace and paranoia, lucidity and hysteria, confidence, fear and fury are all both collective and individual states of mind. Yet the source and fountain of every civilization is in the individual consciousness of the citizen. Family life plays a key role in the connection between the vertical perception of individual life and the horizontal view of larger communities. [5]

From the inner world, social life emerges. Our personal feelings sustain our countries’ happiness or unhappiness. This teaching is present in the philosophical works of classical Taoism. The correspondence between individual life and politics is direct. Centuries before Sigmund Freud, Sir Edward Dyer (1543-1607) wrote:

“My mind to me a kingdom is;

Such perfect joy therein I find

That it excels all other bliss.” [6]

Freud shows in “The Unconscious” (1915), that a human soul has its own sort of topography. The geography of the mind is analogous to physical geography. Many different intelligences inhabit the landscapes of each citizen’s inner being. Every individual has dozens of voices and impulses in his soul, and they live as more or less educated “citizens” in the realm of consciousness.

In the parliament of self-perception, thoughts and feelings represent contrasting possibilities, impulses, points of view and levels of consciousness. There has to be a common feeling and a central government, too.

A superego is necessary that makes decisions in the name of the whole. The governmental superego is supposed to have balance and moderation. It must listen to the silent voice of conscience: it has to express a sense of justice in its decisions.

NOTES:

[1] “The Toilers of the Sea” (1866), look at Part II, Book III, final lines of Chapter III.

[2] From the 1924 essay “The Loss of Reality in Neurosis and Psychosis”, by S. Freud, see the book “The Essentials of Psychoanalysis”, Sigmund Freud, Vintage Classics, selected by Anna Freud, Vintage Books, London, 2005, 597 pp., see p. 568.

[3] On childishness in psychosis, see for instance “The Essentials of Psychoanalysis”, Sigmund Freud, Vintage Books, London, 2005, p. 562.

[4] Read the first pages of chapter six in the book “Freud’s Discovery of Psychoanalysis: The Politics of Hysteria”, by William J. McGrath, Cornell University Press, 1986.

[5] Chapter six in McGrath’s book examines the parallel made by Freud between the “politics in the soul” and the outward politics of a country. The same pages examine Freud’s personal opposition to Theodor Herzl and the Zionist project. Freud died in 1939 and did not see the Holocaust in the 1940s. In part for this reason, the father of psychoanalysis found it difficult to understand the need for Israel, and did not think that the Jewish State should be built as a safe place for Jews to live. Freud may also have felt a bit of envy regarding the strong sense of a healthy future provided by Herzl. The topic should be examined in some other article. Freud and Herzl are two great friends of mankind and both changed human history for the better.

[6] Click to see the poem “My Mind to Me a Kingdom Is”.

000

“The Politics of Hysteria” was published as an independent article in our associated websites on 10 November 2019. It is also available at our blog in “The Times of Israel”.

Related articles:

* “Resistance to Change in Theosophy”, and

* “The Process of Concentration”, the last lone written by Sri Kshirod Sarma.

000