The Role Played by Archives, Books

and Manuscripts in the Work for Mankind

Carlos Cardoso Aveline

It is worthwhile to examine how far the 21st century students of Theosophy must care about libraries, new research and bibliographical issues. Is it not enough to study and try to live the Wisdom as taught in the classical works of the modern esoteric literature?

The theosophical philosophy has a complex view of reality. Life often surprises us, and the right answer to the question is that it is not correct to keep our reading limited to classical books. The original teachings refer the student to a limitless bibliographical horizon, to be explored by each truth-seeker along several lifetimes. The writings of Helena Blavatsky and other classics of theosophy offer criteria and keys to an understanding of universal literature, but they are far from being the only ones we should read.

Through “Isis Unveiled”, “The Secret Doctrine” and in their Letters, the Masters of the Wisdom constantly stimulate the study of the classics in every cultural tradition. They discuss from Dostoevsky to Socrates, from Ancient History to Astronomy or the importance of reviving Sanskrit. The whole field of human knowledge is Their mental territory, and all of it should be gradually grasped, in its essence, by the aspirants to Their wisdom. It is therefore easy to see that having an open mind and developing an eager intellect are two of the practical steps to be taken by every earnest candidate to esoteric wisdom.

In the 19th century, an adept wrote in a letter to Mrs. Laura Holloway:

“Learn, child, to catch a hint through whatever agency it may be given. ‘Sermons may be preached even through stones’.” [1]

There are two extremes to be avoided in the theosophical movement. One is to limit oneself to the mere dead letter of the theosophical classics, thus closing one’s mind to the ever expanding horizons of living wisdom.

The other extreme would be to accept anything written by anyone, anywhere, as long as it is fashionable or seems to be “theosophical”. Thus we would forget that modern Theosophy gives us the best possible ways to look at human knowledge. That includes anything ranging from Science to Philosophy, Art and Religion, from the Vedas to Plato and Shakespeare; from the Upanishads to Leon Tolstoy and the daily newspapers. Esoteric philosophy does not separate us from Life; it gives us viewpoints to better understand it.

Not all that has been published is worthwhile reading. The student must choose his books with care, for there are good and bad books, and all of them radiate occult energies. In an article published by “Theosophy” magazine, one reads:

“Certain books carry with them unseen influences. Consciously aware of it or not, each time ‘The Bhagavad Gita’ is read we step into a stream of wisdom that cleanses perception and restores it to its natural essence.” [2]

It is a sacred challenge to tune in with books which operate on the level of buddhi-manas or spiritual intelligence. The act of reading has always been linked to Religion, although reading was not always about paper and printed books as we presently know them.

In ancient times, for instance, Asian sacred books were written in palm-leaves – as H.P.B. refers in the opening sentence of “The Secret Doctrine”. If we investigate the word “religion”, we see there are two theories as to its origin. The best known explanation says the word comes from the Latin “religare” – meaning “to link again, to bind”, a meaning similar to that of the word “Yoga”. But the other hypothesis, offered by Marcus Tullius Cicero and later adopted by Augustine, is also interesting. It says the word “religion” comes from “relegere”, Latin for “reading again and again”. [3]

One of the main objects of the modern theosophical movement includes a long term, wide-ranging bibliographical task. In the opening of her article “The Organisation of the Theosophical Society”, H.P.B. says that the movement had at first four objects, of which the third was: “To study the philosophies of the East – those of India chiefly, presenting them gradually to the public in various works that would interpret exoteric religions in the light of esoteric teachings.” [4]

Such a “gradual presentation” clearly could not be completed in H.P.B.’s biological lifetime. The task implied defeating any attachment to routine and would have to be developed by different generations of students. The idea remains valid today and did not start in H.P. Blavatsky’s time. For ages, vast libraries and painstaking bibliographical research have been important instruments in the work of initiates, adepts and their disciples. Phrases like “sacred books” and “sacred literature” must be understood in wider and deeper ways than the ones lazy minds prefer. In the Introduction of “The Secret Doctrine”, H.P.B. dedicates several pages to describing the existence of a worldwide network of secret, esoteric libraries.

She writes:

“The members of several esoteric schools – the seat of which is beyond the Himalayas, and whose ramifications may be found in China, Japan, India, Tibet, and even in Syria, besides South America – claim to have in their possession the sum total of sacred and philosophical works in MSS. and type: all the works, in fact, that have ever been written, in whatever language or characters, since the art of writing began; from the ideographic hieroglyphs down to the alphabet of Cadmus and the Devanagari.” (SD, p. xxiii)

As anyone can see, this was no simple or short term task. H.P.B. adds:

“It has been claimed in all ages that ever since the destruction of the Alexandrian Library (…), every work of a character that might have led the profane to the ultimate discovery and comprehension of some of the mysteries of the Secret Science was, owing to the combined efforts of the members of the Brotherhoods, diligently searched for. It is added, moreover, by those who know, that once found, save three copies left and stored safely away, such works were all destroyed.” ( SD, p. xxiii)

Truly esoteric libraries are then both vast and unknown to the public. H.P.B. explains:

“ . . . In all the large and wealthy lamaseries, there are subterranean crypts and cave-libraries, cut in the rock, whenever the gonpa and the lhakang are situated in the mountains. Beyond the Western Tsay-dam, in the solitary passes of Kuen-Lun [Karakorum mountains] there are several such hiding-places.” (SD, p. xxiv)

There must be strong occult reasons to work with such an immense variety of books and manuscripts, whose real contents is mainly at the buddhi-manasic level of human consciousness. H.P.B. goes on:

“Along the ridge of Altyn-Toga, whose soil no European foot has ever trodden so far, there exists a certain hamlet, lost in a deep gorge. It is a small cluster of houses, a hamlet rather than a monastery, with a poor-looking temple in it, with one old lama, a hermit, living near by to watch it. Pilgrims say that the subterranean galleries and halls under it contain a collection of books, the number of which, according to the accounts given, is too large to find room even in the British Museum.” (SD, p. xxiv)

A few pages later, H.P.B. sums it up:

“To recapitulate. The Secret Doctrine was the universally diffused religion of the ancient and prehistoric world. Proofs of its diffusion, authentic records of its history, a complete chain of documents, showing its character and presence in every land, together with the teaching of all its great adepts, exist to this day in the secret crypts of libraries belonging to the Occult Fraternity.” (SD, p. xxxiv)

It might be surprising for some to know of such an enormous amount of bibliographical work in the Brotherhood of Initiates. H.P.B. gives the reader a few more hints:

“This statement is rendered more credible by a consideration of the following facts: the tradition of thousands of ancient parchments saved when the Alexandrian library was destroyed; the thousands of Sanskrit works which disappeared in India in the reign of Akbar; the universal tradition in China and Japan that the true old texts with the commentaries, which alone make them comprehensible – amounting to many thousands of volumes – have long passed out of the reach of profane hands; the disappearance of the vast sacred and occult literature of Babylon; the loss of those keys which alone could solve the thousand riddles of the Egyptian hieroglyphic records; the tradition in India that the real secret commentaries which alone make the Veda intelligible, though no longer visible to profane eyes, still remain for the initiate, hidden in secret caves and crypts; and an identical belief among Buddhists, with regard to their secret books.” (SD, p. xxxiv)

In “Isis Unveiled” (first chapter of volume two), H.P.B. gives a detailed account of how the contents of the Alexandrian Library and other ancient libraries which conventional History says were destroyed have been, in fact, saved into a great extent before the “official destruction” of those libraries took place. Such ancient literature shall re-appear in some more enlightened age, as Blavatsky writes. (SD, p. xxxiv)

One can infer that this global esoteric library is linked to the akashic records of all existing books and manuscripts. In 1884, a Mahatma wrote to Mr. A.P. Sinnett:

“I have a habit of quoting, minus quotation marks – from the maze of what I get in the countless folios of our Akasic libraries, so to say – with eyes shut. Sometimes I may give out thought that will see light years later; at other times what an orator, a Cicero may have pronounced ages earlier …..”. [5]

Reading H.P.B., one sees that in her time the head of such an occult Library was a most venerable sage. She writes about “the Chohan-Lama of Rinch-cha-tze (Tibet), the Chief of the Archive-registrars of the secret Libraries of the Dalaï and Ta-shii-hlumpo-Lamas-Rim-boche …….”. [6]

And again she says:

“In the January number of the Theosophist for 1882, we promised our readers the opinions of the Venerable Chohan-Lama – the chief of the Archive-registrars of the libraries containing manuscripts on esoteric doctrines belonging to the Ta-loï and Ta-shü-hlumpo Lamas Rim-boche of Tibet …..”. [7]

As above, so below, says the ancient Tablet of Emerald. In addition to the worldwide network of fully esoteric libraries, there is a peripherical level of occult libraries, also scattered through many places, which is made by the libraries belonging to various individuals, groups and collective organisms dedicated to classic and original esoteric philosophies. While making in 1888 an assessment of the theosophical work, H.P.B. acknowledged the importance of theosophical libraries and mentioned the example of Adyar:

“Why omit that branch of our work, which many deem the noblest, the founding of an Oriental Library which may become the most valuable in India, if present appearances are not deceptive; the opening of many Sanskrit schools; the publications of the Vedas in the original tongue? ” [8]

Unfortunately, those Adyar appearances did prove to be deceptive. The theosophical Library of Adyar is big and it is useful. On the other hand, in the absence of a true devotion to the essential work, which transcends external forms, libraries can be instruments of self-delusion and personal pride, and the history of the theosophical movement gives us plenty of examples. Attachment to books in themselves is mayavic. The key to their real value is that books are not physical objects only. They are tools for wisdom-transmission which can help one’s consciousness to get to higher realms, if one has enough altruism, self-forgetfulness and common sense.

In a broad perspective, the higher aspects of good theosophical libraries may be connected in one way or another to that “total library” of our present mankind which was mentioned above.

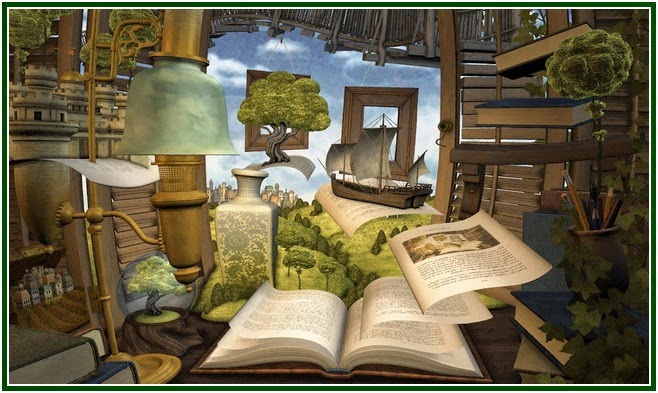

Esoteric philosophy accepts the importance of material aspects of reality. Any library exists in several levels. A classical book on divine wisdom (which may be available in paper or online) is more than a physical object. It helps guide the focus of the learner’s consciousness to the abstract dimension and place where the real records or teachings are. Books are tuning instruments.

Plato’s Dialogue “Phaedrus”, has an interesting passage. After saying that books cannot “defend themselves” by keeping silent, and that they must always repeat themselves, Socrates invites Phaedrus to directly record in his own soul whatever he learns:

“I mean an intelligent word graven in the soul of the learner, which can defend itself, and knows when to speak and when to be silent.”

Phaedrus then asks Socrates:

“You mean the living word of knowledge which has a soul, and of which the written word is properly no more than an image?”

And Socrates answers: “Yes.”[9]

The real importance of classic books of esoteric philosophy is then in the fact that they are the outer image of the real teachings. They open the doors to knowledge.

Superficial reading is of scarce use for beginners. The depth of one’s learning depends on the depth of one’s search, and W. Q. Judge wrote this of those theosophists “who are in earnest”:

“They have learned how all that part of a book which they clearly understand at first is already their own, and that the rest, which is not so clear or quite obscure, is the portion they are to study, so that it also, if found true, may become an integral part of their constant thought.” [10]

An open and vigilant mind is of the essence. One should be able to recognize both wisdom and ignorance under the various forms with which they express themselves in the world. This can be done, once we are able to get the key note of the wisdom for our cycle, which is given by the modern theosophical teachings.

Stones preach sermons to those who can listen. All of Life can be seen as an immense Library, and it is said that there is a great “Book of Life” where everything is recorded by the Lipikas (SD I, p. 104).

In the decisive 21st century, it makes sense for the theosophical movement to have, to preserve and to expand the best possible libraries and documentation centres, in various parts of the globe.

The theosophical effort is often described, at its best, as the lower degree of a much deeper universal brotherhood. In this wide context, every earnest student of theosophy has a specific responsibility. The invisible importance of individual researchers is greater than appearances would suggest, and independent libraries have a deeper significance than superficial minds would like to see. The challenge is to preserve the theosophical classics while constantly researching on how best to live up to their teachings. The task includes all serious students of Theosophy, whether they formally belong to theosophical associations or not.

Mutual help and an unbureaucratic cooperation are unavoidable. The many lines of independent research made possible by philosophical libraries help students avoid the pitfalls of illusion. Thus they can attain wisdom through self-devised efforts.

Classic and active libraries (both in paper and online) are beneficent centers which transmit the keys to sacred energies: they will silently play essential roles in the future progress of mankind, just as they have done in the past, and do today.

NOTES:

[1] “Letters from the Masters of the Wisdom”, edited by C.J., first series, TPH, 1973, p. 150.

[2] “The Student and the World”, in “Theosophy”, November/December 2006, p. 01.

[3] “The Nature of the Gods”, Cicero, Penguin Classics, Penguin Books, London, UK, 1972, 278 pp., book II, p. 152 and, on Augustine, Introduction, p. 54.

[4] “The Organisation of the Theosophical Society”, in “Theosophical Articles” by H.P. Blavatsky, The Theosophy Company, Los Angeles, 1981, three volumes, see volume I, p. 223.

[5] “The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett”, Theosophical University Press, Pasadena, CA, USA, 1992, 494 pp., see Letter LV, p. 324.

[6] “Esoteric Axioms and Spiritual Speculations”, in “Theosophical Articles” by H.P. Blavatsky, The Theosophy Company, Los Angeles, 1981, three volumes, see volume III, p. 328.

[7] “Tibetan Teachings”, in “Theosophical Articles” by H.P. Blavatsky, The Theosophy Company, Los Angeles, 1981, three volumes, see volume III, p. 337.

[8] “Footnotes to ‘A Glance at Theosophy From Outside’ ”, in Lucifer, October 1888, and “Collected Writings”, H.P. Blavatsky, TPH, volume X, 1988, p. 132. The word “Lucifer” is the ancient name of the planet Venus: the term has been distorted by ignorant priests since the Middle Ages.

[9] “Phaedrus”, by Plato [276], in “Plato”, Great Books of the Western World, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., Chicago/London/Toronto, 1952, 814 pp., see p. 139.

[10] “Much Reading, Little Thought”, in “Theosophical Articles”, W. Q. Judge, The Theosophy Co., Los Angeles, 1980, two volumes, see volume II, p. 343.

000

An initial version of the above article was published in “The Aquarian Theosophist”, April 2007, under the title of “The Hidden Importance of Theosophical Libraries”.

000

In September 2016, after a careful analysis of the state of the esoteric movement worldwide, a group of students decided to form the Independent Lodge of Theosophists, whose priorities include the building of a better future in the different dimensions of life.

000