A Short Study in Togetherness

According to the Russian Slavophil Thinker

According to the Russian Slavophil Thinker

Carlos Cardoso Aveline

[Image: a painting by Boris Kustodiev]

Russian philosopher Alexei Khomiakov was the main thinker of the cultural movement known as “Slavophilism”.

His view of life has many a point in common with Helena Blavatsky’s theosophy. He deeply inspired Slavophil novelists whom she admired and wrote about, as Leo Tolstoy and Fiodor Dostoievsky. Tolstoy’s un-ecclesiastical Christianity was inspired by Khomiakov, just as Dostoievsky’s criticism of Roman Catholicism.

Among the classic Russian and Slavophil ideals which have a direct interest to theosophists one can find the concept of sobornost or “togetherness”, and this is the central tenet in Khomiakov’s philosophy. He believed in souls, not in rigid institutions or outer authorities.

In the following sentences from Khomiakov’s writings, as translated by Nicolas Zernov [1], numbers of pages are indicated in parenthesis at the end of each quotation.

Khomiakov wrote:

* “Social order is the external manifestation of the inner attitude of men to one another.” (p. 71)

* “Russian culture puts greater trust in the voice of conscience than in the wisdom of civil institutions.” (p. 73)

* “The world is a creation, it is a Divine Thought, it represents a complete and perfect harmony of beauty and joy. A spirit that violates the law of Divine truth and righteousness puts himself in a state of hostility towards this Divine thought, towards the harmony of cosmic life, and is therefore bound to suffer.” (p. 58)

* “Accord with love alone can strengthen and enlarge our mental vision. We must submit to the law of love, and attune to it the persistent disharmony of our intellectual powers.” (p. 58)

* “Love is not a tendency towards unification; it requires, it seeks, it creates, responses and contacts. Love itself grows and is strengthened and perfected through these responses and communications.” (p. 58)

* “The communion of love is indispensable for the understanding of truth; all true knowledge is based on love, and is unobtainable without it.” (p. 58)

* “A self-centred individual is powerless; he is a victim of irreconcilable inner discord.” (p. 58)

* “The highest knowledge of truth is beyond the reach of an isolated mind; it is open only to a society of minds bound together by love. Truth looks as though it were the achievement of the few, but in reality it is the creation and possession of all.” (p. 58)

* “Only in living communion with others can a man break out of the deadly loneliness of egotistic existence and gain the standing of a living organ in the great organism.” (p. 58)

From a theosophical perspective, Khomiakov is right. However, such a feeling of communion is mainly inner, and secondarily external. It can be attained with regard to all beings while one is in apparent solitude and physical isolation.

On the other hand, there is a loneliness of those who are not alone. Individuals often feel lack of communion while living in a group. The sense of togetherness is not necessarily physical. Perceiving the unity of life is an activity of the higher self, or “the voice of conscience”, as Khomiakov puts it. Perception of unity with others has its roots in silence, and needs a profound individual relationship with one’s own immortal soul. The more one knows oneself, the more one respects others.

Art and Creativity

While blind belief is worse than useless, creativity is connected to altruistic feelings and to renunciation.

Khomiakov wrote:

* “Art is free only when the artist gives up his freedom.” (p. 59)

* “A man who wants to develop his latent creative forces must first sacrifice the selfish side of his personality and thus penetrate into the mystery of common life. He must be united with it by the ties of a living organic fellowship.” (p. 59)

* “A single intellect segregated from living contact with others is barren; only from communion with life can it increase in power and creativeness.” (p. 59)

* “However great our contribution to the common stock, we get back a hundred times more than we give.” (p. 59)

Being a universal thinker, Alexei Khomiakov took the mystical tradition of Russia to one of its highest peaks.

Yet Russian ecclesiastical authorities felt threatened by his view of life. His ideas were considered dangerous. As long as he lived, Khomiakov was seen with suspicion by the official Orthodox church in his country. It was only after his sudden death, on October 5, 1860 (new style) that he won recognition as a Russian theologian. [2]

A Theosophical View of Christianity

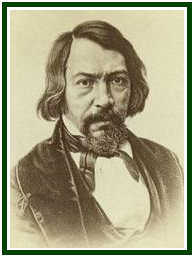

A. Khomiakov (1804-1860)

The reason for that mistrust is in a “political” fact: Khomiakov denied the validity of bureaucratic churches dominated by priests. He taught “sobornost”, the direct togetherness or oneness of life. He wrote that brotherhood must be unrestricted by any legal or intellectual barriers. According to the Russian ideal of sobornost, human beings are entitled to enjoy unity in complete freedom. [3]

As to the Catholic church of Rome, Khomiakov wrote:

“The deification of political society is the essence of Roman culture. Western man was so impressed with it that he could not conceive even the Church save under the form of a State. Her unity had to be compulsive, and hence was born the Inquisition, with its control of conscience, and its executions for misbelieve. The Bishop of Rome was obliged to claim civil power, and eventually he secured it. He acquired the right of juridical control over the part of the church which became known under the name ‘Roman’.” (p. 65)

And also:

“The [Roman] Church, from being a community governed by the free consent of her members, became a State; lay people became obedient servants, and the hierarchy their governors.” (p. 65)

Khomiakov believed that “from Russia, because of its communal outlook, a purer stream of Christianity may flow.” (p. 73)

His views regarding human relations are consistent with those of modern theosophy. A Master of the Wisdom wrote about togetherness:

“A band of students of the Esoteric Doctrines, who would reap any profits spiritually must be in perfect harmony and unity of thought. Each one individually and collectively has to be utterly unselfish, kind and full of goodwill towards each other at least – leaving humanity out of the question; there must be no party spirit among the band, no backbiting, no ill-will, or envy or jealousy, contempt or anger. What hurts one ought to hurt the other – that which rejoices A must fill with pleasure B.” [4]

For Khomiakov, togetherness and solidarity were the rule of life: he died in 1860 while personally treating his peasants and working to alleviate their suffering, during an epidemic.

NOTES:

[1] “Three Russian Prophets”, Nicholas Zernov, SCM Press, London, 1944, 171 pp. Click to see the book in our associated websites.

[2] The Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1967 edition, on “Khomyakov, Aleksei Stepanovich”, volume 13, pp. 332-333.

[3] “Three Russian Prophets”, p. 38.

[4] “Letters From the Masters of the Wisdom”, compiled by C. Jinarajadasa, First Series, TPH, India, 1948, Letter 3, Item III, pp. 15-16. Click to see the book in our associated websites.

000

On the process of togetherness along the path to wisdom, click to see the article “One for All, and All for One”.

000